When it was time to design my own subject for the Facilitating Online Learning #EDUC90970 assignment, there was no doubt my passion project could finally take shape: design a subject for higher education teachers on how to promote self-regulated learning (SRL) in their own subjects.

Based on knowledge acquired during the Graduate Certificate in University Teaching, these were the steps I followed to design a first draft of the subject:

1) Defining context and learners

This subject would be part of a graduate certificate for university teachers, such as the GCUT. Learners would be university teachers with experience in teaching (some with a lot of years of experience!) who are looking to further improve their teaching and learning practice. Cohorts are typically small, around 15 – 20 learners.

2) Defining aim of the subject and learning outcomes

Describing the aim of a subject and its learning outcomes is crucial to achieve constructive alignment. Constructive alignment is when the learning outcomes, activities and assessments are related (Biggs, 2014). This increases the chances of students’ activity to be aligned with the intended learning outcomes of the subject.

Popenici and Millar (2015) have written a very practical guide on how to write learning outcomes. Here are the learning outcomes for this course:

At the end of this course, students should be able to (1) summarise SRL concepts and models, (2) critically evaluate empirical research on strategies to promote SRL, and (3) adapt and apply these strategies to multiple teaching and learning situations in higher education.

3) Defining a pedagogical approach and strategies

I believe people learn creating meaning through their experience, particularly when interacting with others. This is aligned with social constructivism theory (Doolittle & Camp, 1999). Here are eight factors that inform a social constructivist pedagogical approach:

- Authentic learning

- Social negotiation and mediation

- Relevant content and skills

- Understanding of learners’ prior knowledge

- Formative assessment

- Promote self-regulated learning

- Teachers as guides and facilitators

- Encourage multiple perspectives of content

Based on this approach, I chose the following pedagogical strategies:

- Project-based learning: This would allow them to follow their own needs and interest in the subject, in something relevant to their practice.

- Flipped classroom: This would help class time to focus on collaboration, discussion and resolving misconceptions.

- Peer learning: Many benefits have been associated with peer learning (Boud, Cohen & Sampson, 2014). For this subject, this would also be linked to providing them with the opportunity to be exposed to multiple teaching and learning situations through peer assessment.

- Reflective learning: This would have a two-fold benefit for this subject. First, it would address the social constructivist factor mentioned above: promote self-regulated learning. Second, it would be modelling learners on how to promote self-regulated. That is, they would be experiencing putting together a learning diary throughout the subject (Broadbent, Panadero & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2020), which could be one of the strategies they could implement in their own subjects.

A great overview on the definitions and connections of pedagogical approach, strategies, tasks and activities can be found on Peter Goodyear’s paper “Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice.” (2005).

3) Defining tasks and activities

With a clear pedagogical approach and strategies in mind, it was time to define the tasks and how they would be distributed over the weeks. The Conversational Framework by Diana Laurillard (2013) was a great tool to help design the course, as it is very practical and well-linked to the use of technology. So after reading some materials about the ABC learning design method (Young & Perović, 2016), which is based on Laurillard’s framework, I started to work on the course design. I really enjoyed using Treves’ (2020) template in Padlet for this:

This step mainly included defining the main tasks for the subject, which would be:

- Blog posts and comments reviewing SRL main concepts and models: This can be a great way for learners to actively interact with the core knowledge of the subject, while providing an opportunity to interact with their peers. An interesting outcome of this activity is that posts and comments become a learning resource for learners throughout (and beyond) the subject. It also provides multiple perspectives of the content.

- Presentation on chosen instructional strategy to promote SRL: This would require them to conduct an investigation of potential strategies they would implement in their own subject, and putting together a presentation for their colleagues. Peer feedback on their presentations would be another opportunity for them to interact with their colleagues.

- Main project assessment: In the main project, learners would revise their current subject curriculum to include strategies to promote SRL. The whole process would include their peers in the following order: submitting a written project, which would be reviewed by two peers (and they would review two other projects), then a final presentation considering their feedback.

- Learning diary: Learners would keep a reflective diary (with specific SRL prompts) to document their learning journey during the subject.

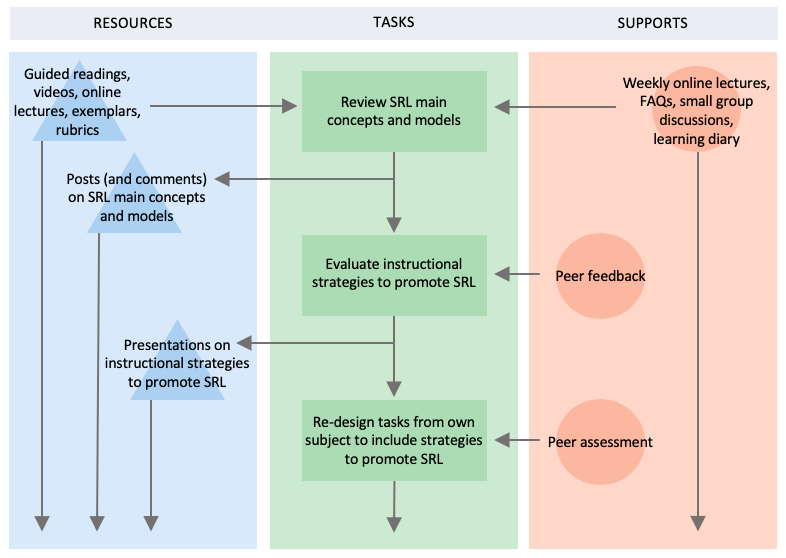

Although the ABC design method was very useful, I felt I needed another type of visualisation to help me better understand the connection between all tasks in a sequenced way before breaking them down into weeks. So I used Herrington and Oliver’s (2002) learning design visualisation, which is divided into resources, tasks and supports, with arrows for sequence. My draft looked like this:

I included learning diary as a support rather than a task as its function would be to promote reflection and awareness to support and improve their learning process. But I guess it could also be considered as a task that would last for the whole course.

I then moved to a weekly distribution of the tasks in Padlet. Below is my final draft:

4) Defining technology to use

First, institutional constraints. The course would be hosted in Canvas, as this is the institution learning management system. So all resources, main communication and record of grades would be there.

For the flipped classroom, Kaltura would be used to produce interactive asynchronous videos. For the synchronous meetings, Zoom would be used, with breakout rooms for small group and pair discussions. I really enjoyed the use of Google Slides by Caitlyn Goudan (see it on this video on the 46min mark) in our class for these collaborations, and also Poll Everywhere, Padlet or Zoom Annotation for interactivity.

For the main projects, which is where learners would make the most use of technology for production, I would provide them with a few options. If they wanted, they could use Canvas ePortfolio for both their Blog Posts and Learning Diary. Or, if they prefer, they could use their own website (existing or new) for this purpose. Or mix and match (Canvas for learning diary and personal website for blog posts). The idea is to provide them with the opportunity to break free from the closed LMS environment and start a broader interaction with the teaching and learning community. This is aligned with concepts related to the Heutagogy (or Self-determined learning; Blaschke & Hase, 2019), a learner centric ecology of resources (Luckin, 2008) and creating a community of inquiry (Garrison, 2007) that could continue after the end of the subject. For the same purpose, I would encourage the use of Twitter. Below is a diagram of the Ecology of Resources for this subject:

5) Defining subject evaluation and improvement

Following the educational research design model (McKenney & Reeves, 2012), this draft of the subject is just the beginning. After its first iteration, it would then be evaluated to further improve its effectiveness in teaching and learning from an evidence-based approach – furthering both practice and theory. Due to it being a subject with a small cohort, evaluation would be quite straight forward. But considering my interest in learning analytics, I would also examine learners’ data to better understand their engagement patterns (I quite like this paper about how to align learning analytics with learning design: Lockyer, Heathcote & Dawson, 2013).

This has been my journey so far creating this subject. I have presented an initial draft to my #EDUC90970 colleagues, which you can see in the video below (or access the presentation here):

Hopefully I will get some useful feedback to further improve the learning design before moving on to the next step: creating a prototype of the subject in Canvas.

References

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA News, 36(3), 5. Retrieved from https://www.tru.ca/__shared/assets/Constructive_Alignment36087.pdf

Blaschke, L. M., & Hase, S. (2019). Heutagogy and digital media networks. Pacific Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 1(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjtel.v1i1.1

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Sampson, J. (Eds.). (2014). Peer learning in higher education: Learning from and with each other. Routledge.

Broadbent, J. & Panadero, E, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (online first 2020). Effects of mobile app learning diaries vs online training on specific self-regulated learning components.

Educational Technology Research and Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-

020-09781-6

Doolittle, P. E., & Camp, W. G. (1999). Constructivism: The career and technical education perspective. Journal of vocational and technical education, 16(1), 23-46. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ598590

Garrison, D R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ842688

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1), 82–101. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1344

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching as design. Herdsa review of higher education, 2(2), 27-50. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/33IWgLX

Herrington, J. & Oliver, R. (2002). Description of Online teaching and learning (Edith Cowan University Online Unit IMM4141 in Graduate Certificate in Online Learning). [Online]. Retrieved August 8, 2020, from Learning Designs Web site: http://www.learningdesigns.uow.edu.au/exemplars/info/PDFs/LD20.pdf

Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies (2nd ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing pedagogical action: Aligning learning analytics with learning design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439-1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479367

Luckin, Rosemary. (2008). The learner centric ecology of resources: A framework for using technology to scaffold learning. Computers & Education, 50(2), 449-462. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.09.018

Popenici, S., & Millar, V. (2015). Writing Learning Outcomes: a practical guide for academics. Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne.

Treves, R. (2020, July 24). ABC Workshops at distance via padlet [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.richardtreves.com/abc-workshops-at-distance-via-padlet/

Young, C. & Perović, N. (2016). Rapid and Creative Course Design: As Easy as ABC? in Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd International Conference on Higher Education Advances,HEAd’16, 21-23 June 2016, València, Spain (Eds) J. Domenech, M. Vincent-Vela, R.Peña-Ortiz, E. de la Poza, D. Blazquez. Available from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.058

Featured image by Laurenz Kleinheider on Unsplash